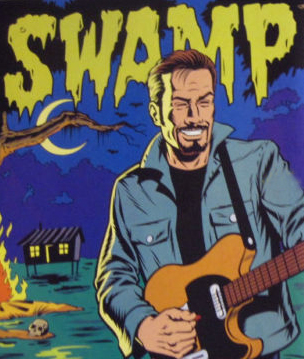

Swamp Twang:Pete Anderson Visits the Darkside with Daredevil

Guitar Player Magazine

March 2005

by Andy Ellis

WHEN IT COMES TO WEST COAST HONKY TONK—the punchy, stripped-down strand of post-war country music popularized by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard—no contemporary guitarist has done more to spread the word than Pete Anderson. Best known as Dwight Yoakam’s lead guitarist and producer, Anderson is the chief architect of the modern honky tonk sound. Released in 1986, Yoakam’s multi-platinum debut Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. was hailed as an antidote to the slick sounds emanating from Nashville’s Music Row. The Yoakam/Anderson collaboration lasted nearly two decades, yielding numerous top ten hits, record sales in the millions, and a 1993 Grammy. During these years, Anderson also produced critically acclaimed albums by such stylistically diverse artists as the Meat Puppets, Rosie Flores, and Michelle Shocked.

WHEN IT COMES TO WEST COAST HONKY TONK—the punchy, stripped-down strand of post-war country music popularized by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard—no contemporary guitarist has done more to spread the word than Pete Anderson. Best known as Dwight Yoakam’s lead guitarist and producer, Anderson is the chief architect of the modern honky tonk sound. Released in 1986, Yoakam’s multi-platinum debut Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. was hailed as an antidote to the slick sounds emanating from Nashville’s Music Row. The Yoakam/Anderson collaboration lasted nearly two decades, yielding numerous top ten hits, record sales in the millions, and a 1993 Grammy. During these years, Anderson also produced critically acclaimed albums by such stylistically diverse artists as the Meat Puppets, Rosie Flores, and Michelle Shocked.

Now flying solo and focused on his own music, Anderson is embracing a more experimental and cinematic sound. On the instrumental Daredevil [Little Dog Records], he drags his sputtering guitar through the swamp to create an edgy, hallucinogenic blend of R&B, roadhouse rock, and spaghetti Western soundscapes. I asked Anderson to describe how he created Daredevil’s colors, and to share his sonic secrets—which include “rinsing” Pro Tools tracks and using classic stompboxes to process parts long after they’ve been recorded.

Guitar Player: Your alt-country fans, expecting more “Guitars, Cadillacs” or “Honky Tonk Man” may be surprised by Daredevil’s somewhat twisted sound.

Pete: That’s why I called the record Daredevil—it felt somewhat daring to chase this muse. But it also felt right, because I don’t like to repeat myself. When I drive somewhere, I take a different route back—even if it’s longer. It’s the same with music.

Guitar Player: You wrote all the tunes and played most of the instruments. How did you begin this project?

Pete: Five years ago, CMT International asked me to do some guitar cues for their TV programs. They gave me titles for the various shows, and, based on those, I scored a bunch of 45-second themes. The budget was small, so I decided to do everything very quickly by myself using Pro Tools. For each cue, I’d create a funky click track using a can, bucket, or bongo, and then I’d come up with a melody. Then I’d add a bit of rhythm guitar, and that was pretty much it. After I turned in the cues, I found myself listening to them over and over in the car because they felt so spontaneous. I realized they were little songs with intros, verses, choruses, and bridges. When it came time to record this album, I went back into Pro Tools and turned the cues into full-length compositions. I expanded the melodies, and I added drums, bass, piano, and solos.

Guitar Player: So Pro Tools’ non-linear recording format allowed you to return to these kernel ideas years later and pick up where you left off.

Pete: Yeah, and that wouldn’t have happened with tape. I felt like I was painting. I’d come to the studio every day, stare at this big canvas and go, “Hmm, let’s put a little ‘blue’ here. Okay, that’s enough. I’m done.” I made loops and played with sound, but stayed very organic. I created all the sounds—birds, frogs, weird backward noises—with guitar. Some people say, “I hate Pro Tools.” But what they really hate are MIDI sequencers. Pro Tools makes it easy to run with your imagination—so, dude, get with it! Actually, I don’t care if you get with it or not, but, believe me, I’m there.

Guitar Player: Do you miss the sonic warmth of analog tape?

Pete: I love that sound, so when I’m done with composing and editing—and if the tracks feel good—I’ll transfer them to a 2″ 16-track machine. Actually, it’s Billy Idol’s old deck. I give the song an analog “rinse,” and then I bring it back to Pro Tools. Check this out. Sometimes, I’ll record bass and drums [onto the analog recorder] at 71/2 ips. There’s more tape hiss than at 15 ips, but at the slower speed, the lows saturate the tape in a cool way. Then I’ll rinse the guitars at 15 ips, which has a more open sound. Thanks to Pro Tools, I can incorporate different flavors of tape saturation and compression within the same song, and that’s so cool.

Basically, I treat this huge analog machine as an effects box. For example, I may record the drums into Pro Tools at 120 bpm, edit them, and then transfer them to tape. Using the deck’s VSO [variable-speed oscillator] knob, I’ll slow the tape down to the tempo I want, and then bring the drums back to Pro Tools. In the process, the tones get really muscular. It works with bass, too. Say the song is in E. I’ll record the bass in F, and then slow it down using the tape machine. When I bring it back, the bass sounds stupid—like I’m using massive strings.

Guitar Player: Daredevil is packed with vibey tremolo, reverb, and slapback echo. Did you use plug-ins for these sounds, or amps and pedals?

Pete: I don’t want to disappoint guitar freaks, but I haven’t used an amp for recording in six years. Line 6’s Amp Farm plug-in does it for me. I’m a Fender Deluxe Reverb guy, right? Line 6 loaned me the original Deluxe they modeled—the mother of the clones—and I did an intensive study comparing Amp Farm’s Deluxe model to its mother. I could never tell the difference. My favorite models are the blackface Twin and the Deluxe, though I’ll sometimes throw in a tweed Bassman. I love how you can do the Steve Lukather thing and put a Deluxe through a 4×12 cabinet. Most of the slapback is Line 6’s Echo Farm—a collection of vintage echo and delay models.

Guitar Player: What about other effects?

Pete: For pedal-steel swells, like in “A Day in the Barnyard,” I use an active Goodrich volume pedal. But my secret weapon is a custom stompbox patchbay that resolves the problems with level and noise that normally occur if you try to run a [tape or hard disk] track through a stompbox. The patchbay can even power any brand of pedal. Now I can route any parts I record through a funky little pedal. I have patch points for an Ibanez Tube Screamer, an MXR DynaComp, and my Robert Keeley pedals. Keeley makes incredible stuff—you have to check out his compressor. A lot of the tremolo is James Demeter’s Tremulator. He nailed the blackface Twin. I compared the tremolo on my pre-CBS Twin to the Tremulator, and they’re identical.

Guitar Player: What’s the advantage of adding stompbox effects after you record a part?

Pete: When the tracks are done, and you hear them in context with each other, you can better determine how much competitive room to grant a particular part by way of an effect. Often, I’ll run the bass through an Aphex Bass Xciter, and then re-EQ the lows to sit just right in the finished song.

Guitar Player: What are your go-to guitars?

Pete: I’m Tom Anderson maxed. My number one is a chambered Tele-style body with three pickups, a 5-way switch, a vintage-style tremolo, and locking tuners. The tone knob is a push-push pot that turns on the front pickup, giving me the chunky neck/bridge tone that’s not available with a standard 5-way switch. Anything you hear on the record with a whammy bar is that guitar. I also have a badass Anderson baritone, the Baritom. My extreme favorite—my saxophone guitar—is an Anderson Cobra with P-90s. It looks like a Tele, but it has a mahogany body like a Les Paul Junior and a 243/4″ Gibson scale. That’s my dog—no, my pit bull.

My main country flat-top is a beautifully aged, silky sounding 1986 Martin herringbone D-28. For fingerpicking, I use a signature model Larrivée PA-OM. Sonically, it’s very competitive—it claws through the track. I have a ’59 f-hole Harmony, which I capoed and played on the outro of “Sweet Delta Sunrise.” On “Daredevil’s Dance” I also used an old Guild converted to high-strung tuning.

Guitar Player: How do you mic your acoustics?

Pete: I put a condenser—typically an AKG C414—six inches out from where the neck joins the body. That’s far enough back to pick up air around the guitar and minimize squeaks and noises. To capture bass coming from the top, I aim a Shure SM57 at the back of the bridge. The mic is set low, pointing up from the floor towards the D and G strings. I also love recording with my 1975 Sony boombox—it has two lapel mics and an aggressive, built-in compressor. We’re not talking high-dollar, silky country sounds.

Guitar Player: Has recording Daredevil changed the way you approach music?

Pete: Yes. For one thing, I no longer see myself as a “record producer”—that term is too rigid. I paint with tones. I’ve also learned to put ideas first. Don’t even stretch the canvas before you have an idea to put on it, or you’ll end up with that green mud from elementary school—too many colors. And I’ve discovered that if I listen hard enough, and exclude all the technical stuff I’ve learned, music will come. It will probably be simpler than I’d expect, and it may not be too challenging, but that’s okay. We’re not here to challenge ourselves, we’re here to make music for others to enjoy. Shut up and listen, and the music will tell you what to play.